Piracy of traditional knowledge: urgent need for equitable solutions

We all identify with our heritage, homes, cultures and traditions. None of us would be happy to see the same misappropriated or exploited by another, lest we lose our identity or claim to what makes us unique.

Traditional knowledge (TK) represents the know-how, skills and practices developed, sustained and passed on from generation to generation within a community. Still, unlike most other forms of intangible cultural heritage, such as rituals and spiritual beliefs, TK can clash damagingly with modern legal systems, finding itself at loggerheads with national Intellectual Property (IP) frameworks. The potentiality and the ethics of a research company receiving a patent that relies on TK to outline the direction taken by R&D is the cause of impassioned debate over how the IP system regards indigenous peoples.

Nature's bounty

TK is commonly associated with using diverse plants as home remedies and for various medicinal applications. However, in Southern Africa, different plants also have deeply entrenched spiritual significance, for example, protecting homesteads against lightning and witchcraft. In the community's eyes, the use and exploitation of such knowledge without asking, not even getting to the issue of offering payment, is tantamount to theft.

Whether termed as theft or biopiracy, it ultimately refers to the same thing – the exploitation of an indigenous group, usually by a multinational corporation that utilizes local practices as a basis to conduct research into the pharmaceutical properties of a plant. Subsequently, they secure patent protection for a drug derived from this research, which then garners billions in revenue.

Arguably, the foremost purpose of the patent system, that which does not expire, is the dissemination of knowledge. Research into indigenous medicines can help spread their benefits from a very small area to the wider world. However, there is no reason for this to come at a cost to the local people.

The indigenous community would likely have never conducted the pharmaceutical research, development and clinical trials necessary to launch a market-ready drug. Nevertheless, the issue is one of equity. The traditional use of the plant may have initially guided the research in the right direction, resulting in the development of a successful drug with an identified active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

Cooperation and compromise

An equitable system would allow for benefit sharing between the indigenous community and the patentee. In light of this, many countries have acknowledged that there is a need for the protection of TK and adequate benefit sharing while also recognizing that the defense of TK does not have to exclude patentability.

There are many examples of TK from all over the world and how it has been used in developing pharmaceutical products. To cite just a few:

- The Central African people of Gabon and Cameroon have used the brazzein berry for generations to help wean infants by letting them "forget" their mothers' milk (presumably due to the sweetness of the berries). A U.S. university isolated and reproduced the protein in these berries and was granted three U.S. patents and a European patent, the protein finding extensive application as an artificial sweetener. Since then, there has been no benefit sharing with the indigenous community for this TK. The knock-on effect has been an economic one for the local people, as the artificial production of the protein has dropped the price of brazzein, causing many local women who drew an income harvesting the berries to lose their jobs.

- In India, the TK of the Kani tribe was used to assist the development of "Jeevani," a medicament to alleviate stress and fatigue. Fortunately, India's patent laws provide protection to indigenous communities. They ensure a benefit-sharing system between the patent holder and the local population achieved through a trust vehicle, which effectively allows the community to share in the profits made from commercializing the patented product or process.

- In South Africa, generations of San people have used the plant Hoodia gordonii on hunting trips to suppress hunger and thirst and boost their energy. This appetite suppressant quality would become of huge interest to a pharmaceutical company, which went on to isolate the API and commercialize it as a drug. In contrast to the brazzein precedent, hoodia was a landmark case for benefit sharing in South Africa, with money held in trust for various San organizations to reap the rewards of this TK.

An often-unseen effect of patenting by multinationals is the devastation of local economies. Synthesized alternatives to naturally sourced compounds can wipe away incomes for farmers and their families. Without profit-sharing schemes, livelihoods may vanish in the face of industrial-scale production.

These examples illustrate that there have been wins and losses in the fight for benefit sharing and the protection of indigenous communities against the misappropriation of their TK and cultural heritage. Yet, there is still another concern: Where the TK indicates a certain medical use, how can that medical indication be patentable in so much as it meets the basic substantive requirements for patentability, namely, novelty and inventive step?

A place for opposition

This question is less of a concern where mainstream APIs are protected, given that patents applied for by pharmaceutical companies are never directed to the naturally occurring compounds or extracts from the plants. Instead, the development conducted by these companies is geared toward the extraction or purification of proteins, the artificial production of proteins and the creation of medicaments (including the testing and formulation of the same). Taking into account such advanced processes, together with carefully crafted patent claims, it is foreseeable that the bar for patentability should be met in such instances, albeit with the possibility that TK may have hinted at a medicinal use.

What happens, though, in the instance of pure natural extracts where the plant's medicinal use is identified by TK? This was looked at in the "pelargonium cases." Pelargonium, also called the African geranium, has long been known in South Africa for its potent medicinal properties in treating respiratory illnesses. In this example, issues were raised regarding both biopiracy and the absence of a benefit-sharing agreement between a European pharmaceutical company and the indigenous community.

Many species of medicinal plants grow in tropical and subtropical regions, with rainforests known to be living hotspots of pharmaceutical potential. However, the most prominent companies making use of such plants rarely originate in these regions, leading to what can be seen as wealth extraction.

The company had created a remedy for respiratory diseases and other medications without negotiating with the community. There were also doubts about the originality of the treatment as it used pelargonium, a plant the local population had been using for generations to relieve similar ailments, which suggested a possible lack of inventiveness on the part of the company. The European Patent Office (EPO) allowed for revocation on the basis of a lack of inventive step, thereby proving a direct interplay between TK and the patent process.

Work still to be done

The TK invalidated the patent, yet one must wonder if this was a true victory. With the TK appropriated and the chance for a benefit-sharing arrangement lost, the community found itself no better off despite the fact that the patents were invalidated. Whilst IP can serve indigenous peoples and benefit them in a virtuous environment, it would, unfortunately, seem as though pirates are still all too common and that Goliath will continue to take advantage liberally and wantonly of older ways of life.

In the absence of regulatory oversight, it is up to drug manufacturers and legal practitioners to wield the patenting system not as a cudgel against local communities nor as a barrier between the bearers of TK and the financial advantages it can promise but as a tool to unite the traditional and the modern worlds in a spirit of fairness and mutual betterment.

Filed in

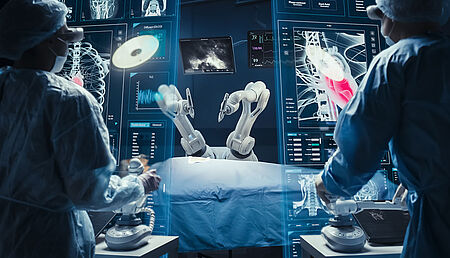

Take an in-depth look at medical devices and how IP will foster, inform and protect more innovative healthcare experiences.