Push vs. pull: patents and access to medicines

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the issue of access to affordable medicines to the forefront of Intellectual Property (IP) debate in recent months. The tension between the patenting and circulation of drugs is nothing new, but it is felt most keenly in the least-developed and middle-income countries, which suffer under heavy burdens of infectious diseases such as Ebola, HIV, tuberculosis and malaria. South Africa, though 36th in the world in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is one such belabored country, with a high level of economic inequality and multiple health crises.

The crux of the matter is that patented medicines are costly, often prohibitively for the poorest nations. Ultimately, this impediment derives from the fact that the research and development (R&D), testing and approval processes required to bring a drug to market are exorbitantly expensive – with the average cost per product exceeding $1 billion USD. Patents provide the incentive to conduct the R&D necessary to develop new medicines, as the patentee can be confident they will be able to recover their costs and reap sufficient reward through profits.

How, then, should the needs of the consumer, that is to say, of patients, for reasonably priced medicines be balanced against the needs of the producer to recoup their massive financial investments? The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) proposes various solutions to this quandary, discussed here using South African law as a case study.

Flexible by design

Article 1 and Article 8 of TRIPS provide for broad adaptability. Article 1, dealing with how member states are to implement the framework appropriately in the context of their national laws, permits countries to afford more extensive patent protections than the minimum standard set by the Agreement, provided that the same is not contravened in doing so. In addition, Article 8 allows members to adopt measures to protect and promote the public interest. Between them, these provisions grant leeway for public health considerations and, consequently, appropriate access to medicines.

Article 66 of TRIPS addresses the availability of medicines and advanced technologies in the least-developed countries. This is vital as many such countries do not have the manufacturing capabilities to produce required medicines domestically, and hence compulsory licensing is not an appropriate way for them to obtain patented products.

Overall, TRIPS provides both flexibility in implementing the Agreement and specific measures for improving access to life-saving medicines, particularly for the most vulnerable populations. However, challenges still exist in fully utilizing these provisions and ensuring equitable access to necessary medications.

Articles 30, 31 and 31bis provide greater specificity in this respect and allow for the unauthorized use of patented subject matter under rigorous conditions as well as for compulsory licensing.

Walk-in rights

Section 4 of South Africa's Patents Act No. 57 of 1978 (the Act) provides for the use of a patent by the state, while Section 78 outlines the state's acquisition of a patent. These provisions are what would be used to facilitate ready access to medicines in the event of a national emergency or pandemic. However, these solutions are only effective when the state can manufacture the drug or import it from a country where patent protection is not in place. Therefore, this mechanism is not ideal for low- and middle-income countries.

Compulsory licensing: reasonability and controlled pricing

Section 56 of the Act permits compulsory licensing in the case of an abuse of rights, with paragraphs 56(c) and 56(e) specifically outlining that unreasonable licensing terms and excessive pricing constitute abuse. These stipulations allow for compulsory licensing to a licensee who will locally manufacture the drug. Once again, as with the walk-in rights, this is premised on the assumption that local manufacturing capability is available, which is not often the case in South Africa.

Open Source Pharma, the Bolar Provision and generic medicines

Open Source Pharma (OSP) is a project akin to the openly licensed software movement, going so far as to describe itself as "Linux for Drugs." This model centers around collaborative R&D and drug trials around the world to produce medicines more quickly and cheaply. We witnessed the speed with which the various COVID-19 vaccines were developed, in no small part due to concerted data-sharing efforts and cooperative research across both the private sector and academic institutions. Partnerships between universities are commonplace, but the idea of combined trials is an intriguing one, as this is where the highest costs of drug development lie. Typically, pharmaceutical companies shoulder these costs and seek to ensure adequate recompense through patents and supplementary protection certificates (SPCs).

OSP proposes an alternative model, where costs are shared among member organizations and any profits from successful drugs are pooled and reinvested into future research and development.

As a parallel option, open-source test data for generics would expedite the drug approval process and allow faster access to cheaper alternatives once patent protection for a medication has expired.

While open test data is not provided for in South African law, the Bolar Provision (Section 69A of the Patents Act No. 57 of 1978) grants a manufacturer of generic medicines the ability to exercise the rights reserved by a patent solely to obtain regulatory approval for the distribution of the product once exclusivity expires. However, each manufacturing company is required to submit its own docket to the medicine regulatory authority, resulting in a great deal of redundancy. Perhaps a middle-ground solution would be to allow the submission of regulatory approvals in other jurisdictions for the same formulation, thereby walking a line between OSP and the Bolar Provision and slightly expediting the process of making generics available. This approach could be considered "open test data."

Substantive examination, patent opposition and the prevention of evergreening

South Africa has a formal examination system as opposed to a substantive examination procedure. This means a patent application is not examined in relation to the novelty and inventive step conditions provided for in the Act, and only administrative requirements are assessed. There is no post-grant opposition period save for full-scale litigation before the Court of the Commissioner of Patents. In contrast to a substantive examination jurisdiction, where the patentee bears the costs for reviewing the subject matter of a patent, litigation is a financially burdensome way for a party to apply for revocation or compulsory license in South Africa. This is, of course, a preferential situation for a patentee in the pharmaceutical industry, as the fees for patenting are low, the validity of the subject matter is not open to immediate question and litigation is discouraged by high costs.

South Africa's patent law has certain provisions that are favorable to the pharmaceutical industry. One such example is the Bolar Provision, which allows generic manufacturers to research and develop their own versions of patented drugs before the patent expires, as long as they do not commercially exploit them until then.

Restricted evergreening is also present in South Africa in that the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC) accepts second medical use applications as well as claims premised on specific and narrow dosage regimes. This practice, coupled with the fact that only a formal examination is conducted, invariably leads to a patent register that contains potentially invalid patents that must be questioned before the courts. Specific dosage regimes and second medical uses are not contentious per se but can be problematic in an environment that does not carry out substantive examinations. Non-allowance of second medical use and / or dosage regime patents would tighten the noose on evergreening and is perhaps an option to be considered in a way that fairly accounts for the R&D and trial costs associated with developing drugs.

Public-private partnerships and tax incentives

South Africa delivers tax incentives for R&D and has laws that regulate public-private partnerships for certain entities and where public funding is used in R&D (Intellectual Property Rights from Publicly Financed Research and Development Act No. 51 of 2008). This legislation can make the innovation landscape difficult to negotiate and less attractive for private partners, given that they control the ownership of patents stemming from such R&D.

It may be interesting to see tax incentives not only for R&D but also for licensing regimes – facilitating lower costs in medication production and correspondingly increasing capacity, but without necessarily raising patent holder profits.

The most feasible solution to affordable medicine access is to be found not so much in national patent law or the TRIPS Agreement but in a broader survey of the economics of drug development, manufacture and distribution. By increasing production volumes, tax and licensing incentives could boost sales figures to levels that a patentee does not necessarily have to forfeit any profit in light of lower consumer-end prices.

A version of this article was first published in WIPR Issue 3, 2022.

Filed in

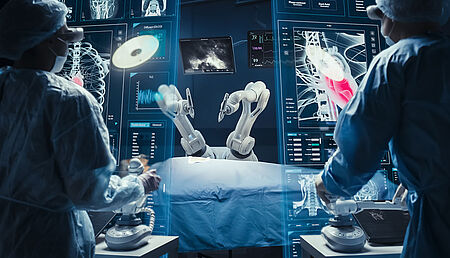

Take an in-depth look at medical devices and how IP will foster, inform and protect more innovative healthcare experiences.